Speeds

THE GEAR RATIO

The distance we travel with one revolution of the bottom bracket is called the gear ratio. The range of gear variations is called gears.

The more meters we want to cover per revolution, the harder we have to push on the pedals. Ultimately, the wheel diameter and the gear ratio are the most important factors. Racers often talk about the gear ratio on their road bike: "I rode up the Cauberg with a 42-18." Because the rear wheels of road bikes have a standard size, you can directly compare gears and gear ratios. This is more difficult on mountain bikes these days. In the 80s and 90s, we also rode with a standard size rim, a 559mm diameter; mountain bikers usually call it 26 inches. The current range of mountain bikes has extra-large tire sizes, designated 27.5 and 29 inches. Especially when comparing different gear systems or wheel sizes, converting to distance traveled is the best way to make that comparison. Things get much more complicated when we install a Rohloff 14-speed hub or a Pinion bottom bracket gear (18 gears). You can find an Excel file for the calculation on the download page. An old-fashioned city bike covers about 4 or 5 meters per revolution of the crank. Racers in a sprint or descent pedal about 10 meters. An ATB with the smallest sprocket 24 at the front and the largest sprocket 32 at the rear (often the lightest gear) pedals about 1.5 m. The speed then quickly drops to 5 km/h and keeping balance becomes more difficult. Even with the same rim diameter, there can still be a difference in the distance traveled; there is a large variation in tire thickness. By choosing wider tires, or simply by increasing the tire pressure, the distance the wheel travels per revolution increases.

FIG.1a Low gear 40x32 FIG.1b High gear 50x12

THE DRIVETRAIN AND GEARS

In the early years, bicycles had a single fixed gear. The drivetrain's efficiency was high because there were no additional friction losses, as the bottom bracket was directly connected to the hub. With a wheel diameter of 1 meter, the distance traveled was 3.14 meters. We consider that a low gear ratio, and to ride faster, people opted for an increasingly large front wheel. They then sought a way to change the gear ratio while riding. The first gear system on a bicycle was therefore located in the hub of the front wheel: a hub gear: planetary gear system, the Crypto-axle from 1878.

As soon as we started incorporating gears, we faced additional losses due to the friction of gears and/or chains. With the introduction of the Rover Safety with chain drive in 1885, the possibility arose to equip the rear wheel with a left and right gear. The rider had to dismount and turn the wheel to change gears. The differences in sprockets were never particularly significant, as the chain had to fit correctly; this could only be achieved by sliding it into the dropout. Yet, this was common practice in cycling for decades.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF DERAILLEURS

Around 1895, a system with an expanding chainring appeared on the market in England. This "Protean 4-speed" system compensated for the difference in chain length with a chain tensioner: an arm equipped with a small pulley with a compression spring, which rested on the chainstay. That same year, a Frenchman also designed a system with such a chain tensioner, but with a movable rod with a fork attached to the chainstay, which shifted the chain from one sprocket to the other: a true derailleur. It was probably never produced, but the idea was already in existence.

In FIGS. 2a, 2b, and 2c, we see designs from the 1930s. Derailleurs were not permitted in the Tour de France until after 1937! These were the common types of derailleurs in cycling until after the Second World War. In Italy, the Vittoria Margherita, see FIG. 2c, was primarily used before the war; this is a similar design, but with the shifting fork reversed above the sprockets, requiring the rider to backpedal to shift. Even before the war, more advanced models existed, such as the Super Champion from FIG. 3 and the vulnerable Simplex from FIG. 4. The front derailleur on FIG. 3 wasn't used by racing cyclists; it was more for tourists and tandem riders. The 1950 Fonteyn catalog provides extensive instructions for the Simplex "with the chain."

Racers in those days used three rear sprockets; apparently, that was enough for a real man.

The first Campagnolo gear systems (see FIG.5a) also had the shift fork reversed above the sprockets; this meant the rider had to backpedal to shift. The rear hub was first disconnected. It could move via teeth on the axle and the rear dropout (see FIG.5b) to compensate for the difference in chain length. The YouTube video shows this.

FIG.6b Navet shift /brake combi (1946)

Shifting a Campagnolo Gambia Corsa.

In 1946, someone even wanted to combine a shifter and a brake (FIG. 6b). After the war, Simplex and Campagnolo front derailleurs came onto the market, which were operated by a lever on top (see FIG. 5b); this meant the rider had to duck deeply and sometimes caused falls. From 1949 onwards, Campagnolo experimented with a rear derailleur with a deformable parallelogram. The definitive version came onto the market in 1953. The shift levers for both the front and rear derailleurs were then mounted on the down tube. The Campagnolo Gran Sport is the most imitated derailleur ever (FIG. 6a)

A new improvement wasn't introduced until 1964. The manufacturer Suntour placed the parallelogram at an angle ("slant parallelogram"); see the right-hand image in FIG. 7a. This kept the upper derailleur pulley closer to the sprockets, allowing for more precise derailleur adjustment. After twenty years, the patent expired, and all manufacturers—Shimano, Campagnolo, Sachs, etc.—suddenly introduced entirely new series, all based on this principle.

In the mid-1970s, Suntour introduced a shifter that operated not by friction (Fig. 7b), but via a ratchet system (micro-ratchet); this was later adopted by many other manufacturers. The next major leap forward was index shifting (shifting in increments). This, too, required considerable experimentation before a satisfactory solution was found. At the end of the 1970s, Bridgestone introduced Synchro Memory Shift, and Shimano introduced the "Positive Pre Select" derailleur. With the latter, the cable wasn't braided, but a rigid wire; you could not only pull it, but also push it. A spring-loaded pin slid over a series of notches on the derailleur. It shifted rather stiffly and was especially popular with people who didn't cycle much.

Shimano's famous aerodynamic AX groupsets also attempted indexing. A pawl ran across a series of steps on the rear derailleur; very vague and easily out of adjustment. In 1984, SIS arrived! Shimano Index System, a system that actually worked! Something for old women, they said at Campagnolo. This arrogance nearly proved fatal. Campagnolo's shifting system was no longer up to date! Within a year, the company went from being a trendsetter to a trend follower. Although I had been riding my touring bike for years with a Suntour derailleur and 'cross shifters, it wasn't until 1986 that I traded the Campagnolo Nuovo Record on my racing bike for the Shimano 600 SIS derailleur. The quality was fantastic, both of the bearings in the parallelogram and of the pulleys, and the shifting was fantastic. Most Shimano derailleurs and shifters are interchangeable. An exception are the first three series of Dura-ace. The rear derailleurs from 1984 to 1993 can only be used with Dura-ace shifters. It does not matter whether the shifter can shift 6, 7, or 8 cogs, the rear derailleur is interchangeable.

Shimano pulled off a masterstroke in marketing: derailleurs, sprockets, and chains all had to be Shimano to ensure optimal SIS shifting.

Not just for road bikes, but also for the new trend: All-Terrain Bikes. With top-tier groupsets like XT and Dura-Ace, they spoiled cyclists, who wouldn't want anything else after a test ride; the standard was set! Every competitor had to shift at least almost as well as the Shimano groupset in its price range to stay in the market. Every innovation, like RapidFire and STI (the shifter in the brake lever), was implemented in the top-tier groupset and then trickled down. Suntour disappeared, Huret and Sachs were acquired by SRAM. Campagnolo is only still a contender in the road bike market; they lost the entire mountain bike market after a single attempt. Shimano rules! Modern CNC production techniques allow for increasingly better integration between chainrings, which limits losses. However, they will then introduce a 9th gear as the highest gear, down from the current 13 sprockets on a cassette.

The cable routing with a bend at the rear derailleur is very inefficient. Suntour, SRAM, and M5 (U-turn-away) have already devised improvements for this. Frame builders had to solder different frame bosses for the Suntour S1; that was just a step too far. In essence, the Suntour was a redesign of the Nivex from '38 and Altenburger from the 1950s.

The integration of brake levers and derailleur shifters has a long history; as early as 1946, the Frenchman Navet applied for a patent for FIG.6b, which places the derailleur shifter on the brake lever. Similar patents also existed in the 1950s. Mavic released a groupset with electronic shifting in the 1990s; Partly due to opposition from the UCI (a battery ban), it wasn't a success. Shimano also tried it around 2015, and then the UCI relaxed the rules; this electronic shifting has since become widely accepted.

We're now seeing the rise of very large cassettes with up to 13 sprockets, 9-52 teeth, and only a single chainring. Whether this trend will last remains to be seen.

PLANETARY SYSTEMS

The oldest way to shift gears is the planetary gear (epicyclic gear), usually located in the hub. The basis for this design comes from clockwork and was already used as a gear system in steam engines before 1800. The Crypto crankshaft for the High-Speed Bicycle (1878) was the first planetary gear system in bicycle technology; it had two gears: a direct drive and a gear. With the invention of the Safety, the drive moved to the rear hub. Around 1900, the first gear hubs for rear axles came onto the market; in England from the manufacturer Sturmey-Archer and in Germany from Fichtel & Sachs.

Epicyclic systems are based on the roller principle (see FIG. 8a); if we place a plank (black) on two rollers (blue), after one revolution, the roller will have covered a circumference of 2 * π * r over the bottom (yellow). The pivot point of the shelf on the base revolves around radius d and covers a distance of 2 * π * d, so twice as much. This might seem strange, but otherwise you could move a cupboard through the house on two separate rollers. We provide everything with teeth, roll the base and shelf into a circle, and get FIG. 8b.

A planetary gear system consists of: a sun gear (yellow), planet gears (blue), the planet carrier (red), and a ring gear (black). Note: The planet carrier rotates more slowly than the ring gear. The planetary gear system is housed in a hub; the hub contains an axle, a hub housing to which the wheel is attached, and a drive head to which the sprocket is attached. The axle is fixed to the frame; in a three-speed gearbox, the sun gear is fixed to the axle. We will now shift by connecting the hub housing and the drive head to the planet carrier or the ring gear. If we connect the drive head to the planetary gear carrier (slow) and the ring gear (fast) to the hub housing, we have an acceleration. If we connect the drive head to the ring gear (fast), and the planetary gear carrier (slow) to the hub housing, we have a deceleration. The sprocket thus turns more often than the hub housing. In our three-speed gearbox, there is not only the possibility to accelerate or decelerate; the drive head can also be connected directly to the hub housing (direct drive). This happens in second gear. Our three-speed gearbox therefore has: 1. A deceleration 2. A direct drive 3. A gear. By making the planetary gear double ("stepped" see FIG. 9), it can, for example, drive a second ring gear. This further expands the shifting possibilities. There is a major disadvantage to planetary systems: all gears that mesh, rotate and transmit forces lose energy due to friction. Usually there is one gear shift in which the sprocket is connected to the hub housing; the yield is then maximum (96%).

Typically, planetary gear bearings are nothing more than plain bearings. The gears are made by sintering metal powder (pressed and baked). The surface is somewhat rougher (increased friction). An advantage is that the lubricants adhere better to the cavities. However, losses due to friction between bearings and gears can be quite substantial, up to 10-20%. In some gears, many gears will be engaged, while in others, fewer. The efficiency of the internal gear hub will therefore depend on the gear selection.

Only Rohloff uses genuine bearings in all its gears; this explains the significant price difference. These gears are made by machining (only the SRAM Spectro P5 Cargo also had machined gears).

The number of teeth on the ring gear is equal to the number of teeth on the sun gear, plus twice the number of teeth on the planetary gear.

The gear ratios determine the steps between accelerations and decelerations. It depends on whether the ring gear or the planetary gears are driven, whether we have an acceleration (>1) or a reduction (<1). If the low acceleration is 3/4 of the fixed drive, then the high acceleration is 4/3 of the fixed drive. This is the case, for example, with the classic Sturmey-Archer AW and copy hubs, such as Hercules, Steyr, Suntour, Brampton, etc.

With drive via the planetary gear carrier, the following applies: the acceleration number = (ring gear teeth + sun gear teeth) / ring gear teeth (>1)

With drive via the ring gear, the following applies: the acceleration number = ring gear teeth / (ring gear teeth + sun gear teeth) (<1).

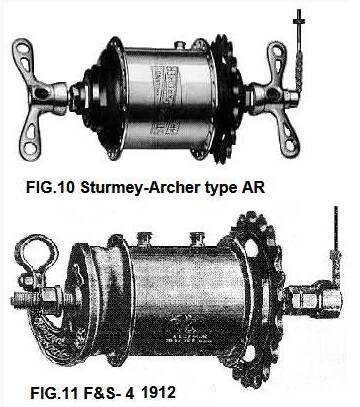

While the derailleur was still in its infancy, planetary gear shifting was already mature. Before World War II, it was also used by cyclists, especially in England. Hubs optionally had wing nuts for quick wheel changes in case of flat tires; there were smaller gear steps ("close ratio"). A top model was the Sturmey-Archer 3-speed AR gear from the 1930s (FIG. 10); in 1939, a 4-speed FM gear was even released.

Making the sun gear very small reduces the gear steps. Unfortunately, the forces transmitted remain the same. The strength of the small gears is insufficient, and the construction becomes unreliable. Therefore, the gear steps in a single-speed planetary gear are large (with a 3-speed gear, a large gear automatically results in a large deceleration). The consequence of a true "close ratio" gearbox, like the AR, is a composite planetary system (stepped planetary gears and an additional ring gear) and therefore some additional losses.

The way you want your planetary system(s) to shift is one of the design challenges. The Fichtel & Sachs 4-speed gearbox from 1912 (FIG. 11) even had three planetary systems; this design was complicated to keep shifting simple.

In the shifting system of the Sturmey-Archer 3-speed gearbox (FIG. 12), a chain operates the check rod. The crossbar passes through the slot in the shaft. The threads of the check rod are screwed into the crossbar. During shifting, the crossbar carries the star clutch (clutch), thus establishing the connection. The spring action ensures that the star clutch returns. If the control pin is not actuated, the hub will shift to the heavy gear due to the spring action. If we combine a 3-speed gearbox with a back-pedal brake, the braking effect in first gear will sometimes be noticeably better than in third (depending on the construction). S.A. has produced many variations on the three-speed gearbox; the AW is the most common. In 1954 S.A. wanted to replace the gearbox with a new design, the SW. It ended in failure, see: https://www.sheldonbrown.com/sw.html

In planetary systems, the fixed sun gear transmits the torque the rider can generate to the frame via the axle. Therefore, the axle of SA in FIG. 12 is flattened to prevent rotation. Many manufacturers therefore add special rings with a locking cam. With the Rohloff (FIG. 13b), a hub often used by strong riders and featuring many low-speed gears, they even opt for quite drastic solutions. A large lever is connected to the axle, which rests on the chainstay. This lever can be omitted if you use Rohloff's own special rear dropouts; these are also equipped with chain tensioners.

The Rohloff is the absolute top-of-the-line hub gear. This is a very well-thought-out design; no corners were cut on the price of the components. Everything must be top quality and extremely reliable; everything is mounted on bearings and runs in oil. The efficiency is comparable to a derailleur, around 95%. At low power levels like 70W (10% loss), the efficiency is much lower than at 300W (4% loss). The gear teeth are made of high-quality machined steel; to save weight, the larger gears are partially made of plastic, with carbon reinforcement. The total weight is approximately 1.7 kilos. The price of the hub is easily €900. The range of this hub is very wide, 526%; the 11th gear is the direct drive. The hub can be shifted both at a standstill and under load. The latter is particularly special, because with Shimano, that would quickly cost you a new gearbox. Both Shimano and Rohloff models allow the entire gear system to be removed.

When more than one planetary gear system is used, it's quite a puzzle to properly distribute the steps between the gears and keep the shifting sequence logical. This is especially true if everything is controlled by a single switch, and 4 to 14 gears are distributed across 2 or 3 planetary gear systems; the Shimano 8-speed gearbox even has 4 sun gears. The shifting action in the axle of these hubs is accomplished with a complex system of cams; nothing is visible from the outside. Even after disassembling the gearbox, it's often difficult, or even impossible, to understand the shifting action and sequence (see the cams, balls, pawls, and springs of the Rohloff hub shifting system in FIG. 13a).

The YouTube video at the bottom of the page attempts to explain it.

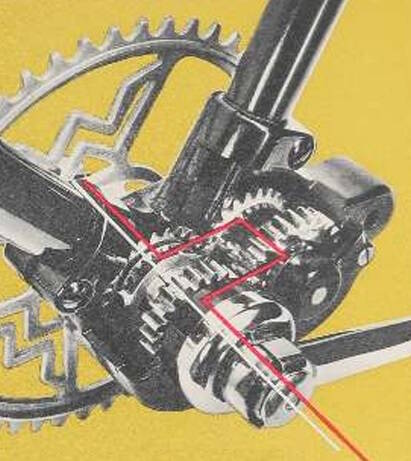

The photos on the right show the inside of a SRAM Spectro P5 with two shiftable sun gears, three stepped planetary gears, and one ring gear.

In FIG. 14a, we see the cams on the axle at B. These can lock the small sun gear A or the large C; these are actuated by the control pin. Both sun gears are permanently engaged with stepped planetary gears. There are two sets of pawls: one on the right side of the ring gear (see FIG. 14c+e), and one on the left side, inside the hub, where the pawls of the planetary carrier are located (see top of FIG. 14f). In FIG. 14d, we can see the two rows of cams where the pawls engage the hub shell.

The switch is operated via the click box ( 4 in FIG. 15a). Here, the switch cable operates the dual control pin via a cam disk. The plastic fixing bush with guided cam ensures the connection between the control pins and the click box. The steel control pin ( 1 in FIG. 15b) slides one of the sun gears onto the fixed cams (B in FIG. 14a). The aluminum tube surrounding it ( 2 in FIG. 15b) operates the clutch between the drive head and the planet carrier or ring gear. In the first two gears, the drive is via the left-hand pawls (planet carrier) and in the other three via the right-hand pawls (ring gear).

The SRAM 7-speed gearbox operates the same way. The only difference is that it has three shiftable sun gears and the planetary gears have three stages.

The construction of the SA 7-speed gearbox is somewhat similar to the SRAM (both have three sun gears).

The construction of the Shimano 7-speed gearbox is completely different; it has four sun gears, two ring gears, and two planetary carriers. Because there is no direct drive and the forces sometimes pass through both systems, the efficiency in some gears is less than 80%, and on average around 85%.

The SA 8-speed gearbox is completely different again. The first gear is the direct drive here; this means that all other gear ratios are true gears. So choose a very low ratio, such as 32 in the front and 24 in the rear, with this gearbox.

In the early 1990s, Sachs was working on a 12-speed gearbox; this would be the great leap forward. Significant investment was made in development and automation, but the result was a relatively expensive and heavy hub. There were some teething problems and financial difficulties; this made Sachs ripe for a takeover by SRAM. After a year, SRAM ceased production, development, and support of the product.

The Nexus 8-speed gearbox is a four-speed design, with a direct drive fifth gear and three gears. By equipping the planetary gears with needle bearings and the direct drive, the average efficiency of this gearbox exceeds 90%. Furthermore, the range (the difference between the highest and lowest gear) of the 8-speed gearbox has increased to 307%, compared to the 244% of the 7-speed gearbox.

In 2010, the Shimano Alfine 11-speed gearbox was launched. It weighs approximately 2kg; lubrication is provided by an oil bath; the range is 409%; and the price is approximately 300 euros. This makes it a formidable competitor for Rohloff, although the latter scores slightly better on all counts except price. Electronic shifting and disc brakes are among the options. Sheldon Brown also has a wealth of information:

Shimano Nexus and Alfine: https://www.sheldonbrown.com/nexus-mech.html

SRAM 8 and 9 gear boxes: https://www.sheldonbrown.com/sram-g8.html and https://www.sheldonbrown.com/i-motion-9.html; older SRAM hubs from 1999 (3 to 12) are listed in the PDF on the download page.

More about hub gears can be found on the following pages:

FIG.15c Modern two speed combined with derailleur from Classified

COMBINING DERAILLEUR AND PLANETAIRY GEAR

The Sachs Orbit was a two-speed hub gear, also equipped with a 5-, 6-, or 7-toothed cog block. This allowed for the elimination of the second chainring and front derailleur. Later, a 3-speed gearbox was combined with a 7- or 8-toothed cassette in the DualDrive, first from Sachs and, after the acquisition, from SRAM. Unfortunately, you combine not only the advantages of both gear systems, but also their disadvantages. Only in certain cases, such as an Alleweder recumbent trike, have I opted for this solution.

The Efneo GTRO Gearbox 3 Speed in the bottom bracket is another option to imitate a 28/40/50 Triple Crankset. Can be combined with a rear derailleur or internal gear hub. The first gear is direct drive, the second is +43% and the third is +79%. There is now also a Belgian company with a wireless 2-speed gear in the rear hub. https://classified-cycling.cc/en/ The high gear is direct drive; the low gear shifts 32% lower. The battery in the hub can be charged via micro-USB, sufficient for 10,000 shifts. See FIG.15c.

FIG.16 Rotating balls

THE CONTINUOUSLY VARIABLE TRANSMISSION

Since 2007, a continuously variable gear hub has been available: the Nuvinci/Enviolo. This is not an epicyclic system, but a traction drive.

This CVT shifts using rotating balls instead of gears, as in conventional gear hubs. The special traction oil in the hub plays a key role in the transmission. Depending on the distance between the contact point of the input disc (connected to the gear, right) and the output disc (connected to the hub, left) relative to the axis of the balls, the gear shifts more easily (fast gear, small radius) or more easily (slow gear, large radius). The contact point is infinitely adjustable using a simple rotary switch integrated into the handlebar. A slight movement is enough to adjust the transmission to any desired setting. This provides an almost infinite variation in the number of gears.

The hub's efficiency is moderate in the mid-range (85%); in the lowest or highest gears, losses are even considerable, especially at high power. A new version of the hub has been available since 2011, weighing only 2.5 kg and offering a range of 360%. The technical capabilities of this hub are also increasing, such as disc brakes and dropouts. In terms of performance, this puts it in a competitive position with the Shimano Alfine 8 or 11 gear box.

A new development is the Enviolo Harmony gear box, which automatically adjusts the gearing based on a certain, adjustable pedal pressure. This Harmony gear box is primarily intended for installation in e-bikes and has great potential: produce according to capacity, use according to need (an old socialist ideal). The Harmony is a particularly good solution when using a mid-motor, as the gear box shifts well under load; this is a weak point with Shimano. The Bosch mid-motor is a good combination with this. See also the video at the bottom of the page. Make sure the batteries don't run out, because the training effect of this combination is significant.

Tests have been conducted with several of the described gear hubs, and the efficiency figures can be seen in a graph by German engineer Andreas Oehler. Some knowledge of German is helpful when reading that website, but the graph gives a good overview. The thick lines represent a (sports) power output of 200 watts. At very low power outputs (50W), the efficiency always decreases (thin lines).

Meanwhile, the manufacturer Nuvinci has chosen the name Enviolo and has focused more on e-bikes, with considerable success.

FIG.17a A French bracket gear 1903 (Magnat-Debon).

BOTTOM BRACKET GEAR SYSTEMS

While with a hub gear, the torque is more than halved by the transmission, with a bottom bracket, it flows through completely. A characteristic of all bottom bracket gear systems is the fact that the sprocket can rotate faster or slower than the bottom bracket.

In 1878, the era of the High-Bicycle, the Crypto-Axis already existed. This planetary system had two gears and was, of course, both a hub and a bottom bracket gear. Peugeot's first catalog, published in 1886, already features a bicycle in which such a bottom bracket was used in a Safety. In this design, the shifting action was on the right, while on the High-Bicycle, it was supported by the front fork. To compensate for the loss of this support point, a large bracket was placed over the bottom bracket, and the sprocket moved to the left side of the frame.

In the early twentieth century, the Sunbeam two-speed gearbox (a planetary system) was successful in England. In France, there was a three-speed gearbox with a sliding gear block (see FIG 17a); this one remained in production for 25 years, and was only supplanted by cheaper derailleurs in the late 1920s.

Look at the middle figure in FIG.17a; the large cog on the left is attached to the sprocket. There is an auxiliary axle, parallel to the bottom bracket. The small cog on the left on the auxiliary axle is always in contact with the large cog on the bottom bracket. There is a sliding gear block on the bottom bracket; in the middle figure, the middle cogs are in contact with each other. The drive forces go via the bottom bracket to the auxiliary axle, and drive the sprocket via the small and large cog on the left. The sprocket therefore turns slower than the bottom bracket: an easier gear (actually a deceleration). The large cog on the left also has teeth on the inside; when we push the block in, the bottom bracket takes the sprocket with it: the heavy gear. If the gear block goes all the way to the right, the auxiliary axle turns even slower and we are in the lightest gear. Shifting must be done carefully, because the teeth have to slide into each other! The Adler 3-speed gearbox also had that problem.

Before the war, several German manufacturers also had bottom bracket gears: Bismarck had two freewheels and a countershaft; Wanderer and Brennabor were constant mesh 2-speeds, Adler a 3-speed, and Rappa a 4-speed (FIG 17b).

The Leeuwarden bicycle factory Phoenix, see http://www.rijwiel.net/phoenixn.htm, installed a true 3-speed gearbox (not a planetary system), the Mutaped (Swiss), from the late 1930s to around 1956. This required a special large bottom bracket; see FIG17c. Also found in the museum in Biel (Swiss).

The Vilex-B.U.E.C. is a beautiful French design from 1949: a five-speed gearbox with a fixed drive, brake, and freewheel in the bottom bracket (see FIG 17d). Working examples are very rare.

FIG.17b German 2-speeds: Bismarck, Wanderer (1935), Brennabor and the Rappa 4-speed from 1938

FIG.17c Phoebus Mutaped a Swiss design end '30's . The pawls 11, 12, and 13 in the axle shift the sprockets 30 , 31 and 32 via commandcam 16 .

FIG.17d Vilex - Boite Universelle d’Equipements pour Cycles, a 5-speed (1947-'52).

FIG.17e Modern shifting from Germany 2013 : the Pinion.

In 2013, this modern internal gear bottom bracket (see FIG 17e) was put into production; the German Pinion has 18 gears and a range of 636%! The weight is 2.7 kg. Of course, you have to build special frames for it. The efficiency is around 91%, see A. Oehler; slightly less than Rohloff, but certainly as good as other internal gear hubs and with a larger range. Meanwhile, there is also a 12-speed and two 9-speed gears: wide ratio (XR), and close ratio (CR). A French look-a-like: https://www.effigear.com/en/114-gearboxes

Bottom bracket gears are often combined with belt drives: http://www.gatescarbondrive.com/ ; a trend we also see with Rohloff and Shimano Alfine hub gears.

The rear frame of these bikes must be split, because the belt cannot be separated. They last a long time, but compared to a well-lubricated chain, you do lose some efficiency.

A gear box that is rarely seen in the Netherlands is the Schlumpf 2-speed. This is not located in the hub, but on the bottom bracket. You change gears with this 2-speed by sliding the bottom bracket to the left or right. The gear steps are large; especially useful for a folding bike (e.g. Brompton) or recumbent bike (extra light or extra heavy gears). Schlumpf also offers a front wheel hub with bottom bracket, and with a 150% gear, type FSU, for unicycles or imitation high-wheelers; with a tire choice of 60-787, you still get a gear ratio of 4.27m. In the 1990s, there was also an epicyclic 4-speed gear box from Bridgestone (the FM-4); reasonably popular in the USA and Japan, but it was never marketed in Europe. A comparable Shimano FM-5 from that period never made it beyond a few years at Miyata. The Strida folding bike sometimes uses a Sun Race bottom bracket gear: the Sturmey-Archer KS3.

Shimano has a patent for a derailleur gear system in the bottom bracket; of course, a special bottom bracket is also required here. As a major OEM manufacturer, they can afford such a system; they set the standard! The bolt pattern is said to be identical to the mounting pattern of their e-bike motor, which makes the bottom bracket's use in mass production more likely.

The details of the patent point to a design for the mid-market segment, but it is not yet clear whether this system will actually go into production. In fact, it is a formidable competitor to their Alfine 11-speed hub. The cassettes contain seven sprockets with 19-21-25-29-33-37-41 teeth; the lower cassette shown in FIG. 20b can shift one notch to the left. A derailleur shifts diagonally via D2. So there are two positions for the chain on the lower cassette; only one on the last sprocket. So there are 13 "gears". The chain always runs in a straight line; the use of an oil sprocket increases efficiency. That will be between a derailleur and a hub gear, approximately 90-92%; the range of the sprocket is 467%.

FIG. 18a This Shimano 13 speed will need a special bracket too.

FIG.18b Inside the Shimano gearbox are two cassettes and a chain.

FIG.19a As-aandrijving Spalding Chainless 1898

FIG.19b CeramicSpeed shaft drive with 13 speeds.

Oval chainrings are also over 125 years old. Shimano tried again in the mid-1980s. In France, Polchlopek produced oval chainrings on a limited scale for about 20 years for a small group of enthusiasts.

Rotor has even successfully had champions ride their products over the past 10 years. The advantages, if any, are barely measurable. The disadvantages, such as getting used to the "unround" rotation and the higher price, are manageable. Recently, the German company CyFly designed a crankset variant with a moving crank position: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TQ2VBt46_Zo

Technically all very nice, but expensive, and a special frame is required for this application. This makes commercial success more difficult.

Completely new drivetrain concepts are coming from Denmark.

Here, the bottom bracket drives a generator (dynamo), and the electricity you generate by pedaling powers the electric motor in the rear wheel. This eliminates the need for a chain and sprockets; combining it with a battery is now very simple. Maintenance is also much easier. This could be a very interesting product for commuters on e-bikes, but it hasn't been on the market for very long. I doubt whether the efficiency is sufficient for a regular bicycle. It might be a good solution for a city or folding bike.

Shaft drives have been around for 125 years, of course, but their efficiency is usually less than 90%. A new approach to the solid-shaft drive is CeramicSpeed Driven, also from Denmark: https://www.ceramicspeed.com/en/driven/

Unfortunately, special frames have to be built for them. The manufacturer claims that the CNC milling machine spends 8 hours on the rear sprocket with 13 shift positions and horizontal teeth.

CeramicSpeed claims to halve the losses compared to a good derailleur; as we've seen, it has about 4% loss. This means an efficiency of 98%. Sounds good, but will that last in a sprint? And how much should that bike cost?

FIG.19c CyFly: moving cranks with oval chainring .

ELECTRONIC SHIFTING

The first company to market an electronic shifting system was Mavic in 1992. In 1999, the system even became "wireless": the Mavic Mektronic. More than 10 years later, other manufacturers like Shimano and SRAM also entered the market. Incidentally, Campagnolo had already applied for a patent for electronic shifting in 1994; see the patent application at the bottom of the page.

Mavic already used a small dynamo in a derailleur pulley in 1992. A design that Campagnolo shamelessly patented in this patent as well; see FIG. 21b, no. 31.

Wireless shifting is also used today in hub gears like Classified, Rohloff, Shimano Alfine, and Pinion.

FIG.20a Mavic Mektronic wireless shifter.

FIG.20b Campagnolo dynamo

Want to know more?

old internal hubgears

VRIJWEL ELKE OUDE REMNAAF EN VERSNELLINGSNAAF IS HIER TE VINDEN! http://sheldonbrown.com/sutherland.html ; en Internal-Gear Hubs (sheldonbrown.com)

De officiële geschiedenis van SA: http://www.sturmey-archerheritage.com/index.php

De S-A.Master Catalogue 1957 : https://www.icenicam.org.uk/library/Sturmey-Archer/Hub_master_catalogue_1957-04-09.pdf

Op rijwiel.net vindt u deze interessante pagina: http://www.rijwiel.net/4versnln.htm

Oude SA-naven: http://www.sturmey-archerheritage.com/index.php?page=history&type=technic ; http://hadland.wordpress.com/category/cycle-technology-history/

Info over Fichtel & Sachs Torpedo-naven: http://www.3gang.de/3-gang/index.htm ; http://www.radhaus-freiburg.de/tech/getr_srm.htm

Veel handleidingen en onderdelen van Fichtel & Sachs: http://www.scheunenfun.de ; http://www.velo-classic.de

Old derailleurs

VRIJWEL ELKE OUDE DERAILLEUR IS HIER TE VINDEN! http://www.disraeligears.co.uk/Site/Home.htm

Een belangrijk boek over de ontwikkeling van de derailleur: The Dancing Chain: History and Development of the Derailleur Bicycle [Berto, Frank]

Deze zelfde auteur schreef ook een artikel over Suntour, te downloaden op deze pagina https://www.mechanischehirngespinnste.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/sunset_of_suntour.pdf

Heel veel archiefmateriaal van Campagnolo: http://www.campyonly.com/history/catalogs.html

Onderlinge uitwisselbaarheid van onderdelen bij Shimano: http://sheldonbrown.com/k7.html#dura-ace.html ; http://sheldonbrown.com/dura-ace.html

Rem- schakelhandles: https://kuromori.home.blog/an-incomplete-history-of-the-brifter/

Versnellingen van deze tijd....

Het moderne gebeuren van Campagnolo: http://www.campagnolo.com/jsp/en/index/index.jsp

Shimano: http://cycle.shimano-eu.com en http://www.paul-lange.de/service/Support/Shimano/Support.php#anker_werk

Informatie van Shimano voor monteurs: http://si.shimano.com/ en voor SRAM: http://www.sram.com

Een traploos regelbare versnellingsnaaf: www.nuvinci.com

Een tweebak in de trapas: www.schlumpf.ch

Rohloff, als kwaliteit het enige is dat telt: www.rohloff.de

Een nieuwe speler op de markt met een onderhoudsvrije naaf: https://www.3x3.bike/en/nine-gear-hub